Creativity Series Part I:

Creativity is an ability that only humans possess. Is that still the case? Recently, another species has been mentioned in relation to creative achievements: Generative Artificial Agents.

Is GenAI creative? First of all: we are not going to answer this question here. Before we can even talk about it, it’s important to get to grips with the concept of creativity. What is creativity?

Of course, no single blog article is enough to answer this, if it is possible at all. In this blog article, we take a closer look at the concept of creativity. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that we cannot cover all areas, thoughts and scientific findings on this topic and that there are still many unanswered questions in science.

We start with a general definition of creativity: the creation and realization of something new, unique, original and useful. For a group of people, in a defined period of time and context. Some other definitions place additional requirements on creativity. The US Patent Office, for example, includes the effect of surprise in decisions on patent awards.1 Still others call for the dimensions of elegance and style to be taken into account when defining creativity. Creativity is not so always easy to recognize or evaluate. What is perceived as creative is subjective. A basic distinction is made between different levels of creativity.2

When children draw a picture for their parents at school, we – at least the people who are not the child’s parents – are aware that no Picasso was at work. The fact that the picture is original is possible because every child paints slanted head-foot pictures in a unique way. This is the mini-c level of creativity. The main benefit is the individual learning effect and a positive feeling in relation to one’s own performance.

The next level up is called little-c. Here we can already recognize a clear benefit. This level relates to creativity in everyday life in order to simplify our lives. For example, we are on our way home by bike and suddenly have a flat tire. We are still a long way from our destination and have to somehow manage to get there before it gets dark. What options do we have to solve this problem? Little-c creativity is not groundbreaking, but it is useful.

One step further we come to Pro-c. This level of creativity can largely only be achieved by experts in a specific domain. Some speak of a ten-year rule. To reach this level of creativity, an expert must have spent at least ten years in an industry. An example would be the development of a medical app for blood analysis.

Last but not least, we have the Big-C level. Very few people in the world reach this level. Big-C includes things like the Internet, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 or the GIF format. In other words, creative solutions, people and processes that are highly original, useful and recognized by a large percentage of humanity.

The time component plays a role in the perception of everyday creativity. Daily creativity occasionally has to be achieved in real time. Referred to as “improvisation”. It is particularly challenging when we create and implement original and useful solutions under time pressure, such as the work of an emergency paramedic or improvisational dance.

In contrast to everyday creativity, we find higher levels of creativity in a specific domain or social context. Solutions in this area have much more far-reaching consequences and require considerably more time, knowledge, experts and long production and evaluation phases. The motives are mostly different. Time travel, for example, is neither an implementable nor low risk solution to any everyday problem we had so far. Of course we could use it to travel back in time to prevent the flat tire. But what if I have a traffic accident in my new past. It can have far-reaching consequences and will take a long time to be implemented – if ever. And just in case anyone here sees time travel as a bad example. It’s a problem for which many creative answers have already been generated by experts from one domain. These include, for example, quantum mechanics, wormholes or the theory of relativity – to name just a few.

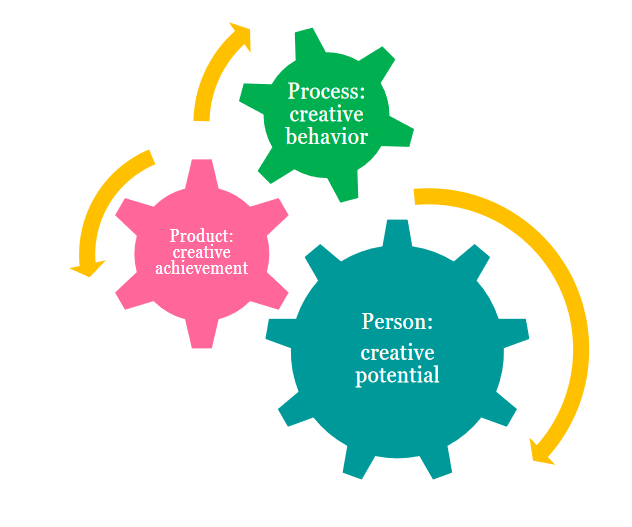

When we talk about something being creative, we commonly refer to different aspects:

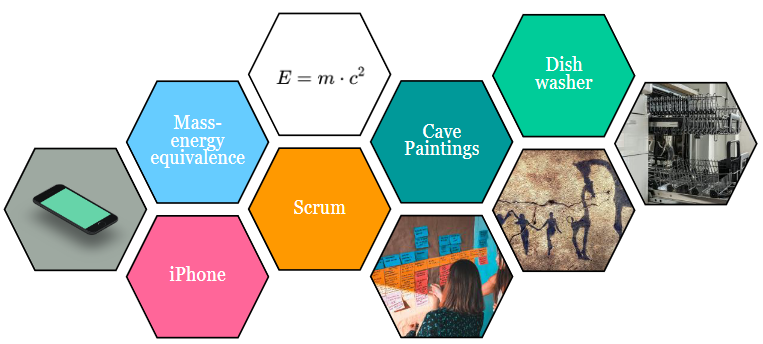

A creative product can be anything that is novel, original and useful. This does not necessarily have to be a painted picture or composed song. A mathematical formula or a household appliance can just as easily be considered creative.

But who decides whether something is creative?3 Everyone can decide that for themselves. Sometimes, as a layperson in an industry or scene, it is difficult to make a truly qualified assessment of whether something is original and has added value. Added value can as well mean that I enjoy looking at something or being inspired by it.

Teresa Amabile, a professor at Havard Business School and well-known psychologist, developed the Consensual Assessment Technique (CAT).4 This method is often referred to as the “golden standard” of creativity measurement and is considered to be one of the most effective methods for measuring creative performance. The method can be used in many different disciplines and in relation to a wide variety of products.

In this method, a group of jury members is appointed. Each evaluates individually and in isolation on the basis of various dimensions. The subjective views of all jury members are then collected and combined, resulting in an overall assessment. Instead of static questionnaires, the special thing about this method is that the jury members themselves are experts in the relevant domain. The most difficult part of the method is to determine the most suitable experts. With the Consensual Assessment Technique, subjective viewpoints and preferences can be taken into account, as everyone has a different idea of what is creative.

Whether a product is perceived as creative depends on us. We pass on and develop ideas over generations. Some forms of creativity improve survival. The invention of weapons was most likely a creative response to the need for protection from enemies and predators. It may be that at some point, in evolutionary terms, we no longer need them and they lose their perceived creativity (great article about evolutionary approaches of creativity).5 Cave paintings and axes made from branches and stones were certainly once “all the rage”. Today, many once groundbreaking creative achievements have been integrated into our everyday lives as a matter of course, developed beyond recognition or have become useless. The cloud or vacuum-cleaning robots are the creative products of modern times. But how do we come up with these ingenious, creative products? It can happen in very different ways. Let’s look at two examples:

Grace Hopper – The first Compiler

Grace Hopper (or Grandma COBOL) had a doctorate in mathematics and mathematical physics and wanted to join the Navy. Via the exceptional “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services” program, she finally made it into the military in a roundabout way. Here she made herself indispensable even after the war. She held on to her belief that it was much easier for people to give computers commands in natural language and developed the first functioning compiler that translated written language into the computer coding “0” and “1”. Side note: She also coined the term bug – our modern term for computer errors.6

Hedy Lamarr – Wi-Fi and Bluetooth

Hedy Lamarr was known as the most beautiful woman in the world and Hollywood star in Snow White and Cat Woman. Additionally, she was an inventor. During the Second World War, she was involved in a discussion about whether torpedoes should be remote-controlled via radio frequencies, as these could be manipulated too easily by the enemy. Together with her friend and composer George Antheil, she recognized the connections between the latest musical findings from her work with several pianos and the associated ways of dealing with frequencies. Together they developed the frequency hopping method. This is a forerunner of frequency hopping spread spectrum (FHSS), which is widely used today for wireless communications such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth.

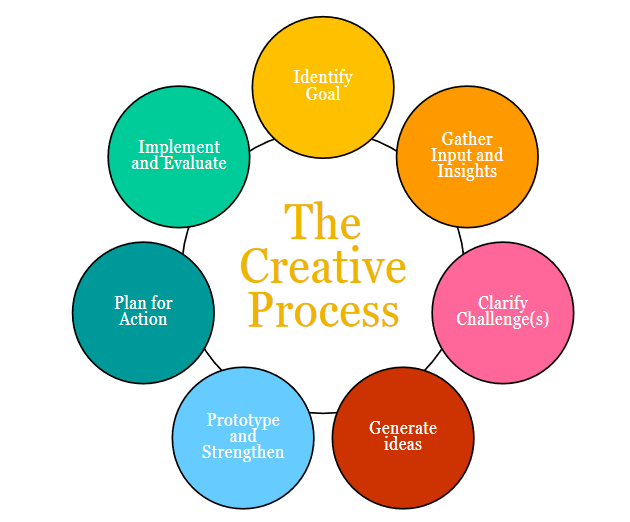

Of course, exceptional circumstances such as wars, temporary funding programs or buzz topics on the investor market and the resulting financial resources are oftentimes the decisive factor in whether we can pursue a more or less great idea. It often takes the right combination of people in the right place at the right time. An idea alone does not lead to a creative result. Sometimes chance plays an important role. So it takes more than a fixed idea to create a creative product. In order to create something useful and original, it is necessary to identify what is needed in the first place. A goal must be defined. We need to know the circumstances and the domain. This requires experts. We need to set ourselves a clear task and find many potential solutions. This is probably where most people see “creativity” as such. We have to select individual ideas from these and actively pursue them.

We then need to evaluate whether we have actually achieved our goal with our product or process. Can we get our dishes clean in under three hours without having lifted a finger? Can we talk to a person in real time even though they are on another continent during the conversation? Have we made our listeners dance happily when they hear our song?

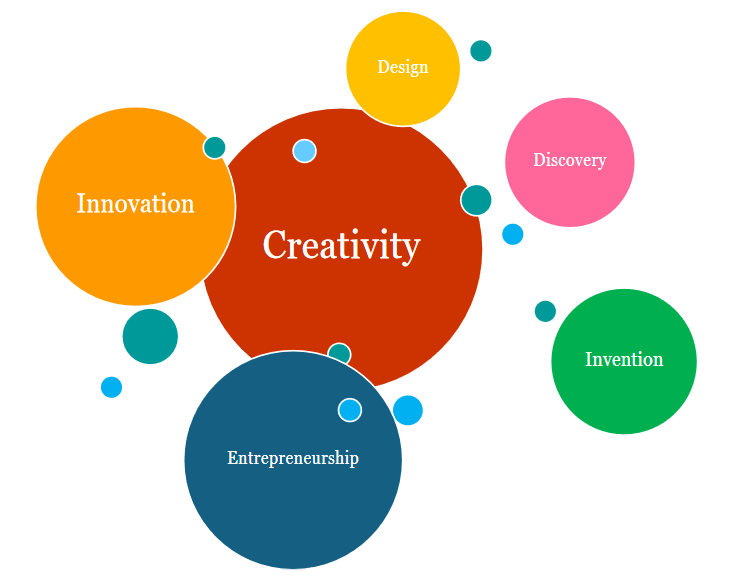

The concept of creativity is often not clearly separable from other concepts.

Here we see a family of concepts that are strongly interconnected. We see innovation, design, discovery, invention and entrepreneurship.7 Some scholars see creativity as the umbrella concept of all other related concepts. Others see innovation as the umbrella concept, with creativity playing an exclusive role in idea generation and selection of ideas for implementation. Of course, we cannot clearly differentiate between these concepts. There are various definitions of each concept. We have tried to work out the subtle differences. Let’s take a closer look at the individual concepts:

Discovery

A discovery is when we find something that is unexpected and causes a surprise effect. A classic example of a discovery is the universal law of gravity. Even before Sir Isaac Newton, millions of people have seen apples fall from trees. Moreover, hundreds of people have certainly been hit on the head by an apple. Nevertheless, Newton was the first to discover why this happens. In science, a discovery therefore means seeing something that everyone has seen before, but at the same time think about it in a way that no one else has thought about it before.

Invention

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) defines an invention as “the creation of a new technical idea and the physical means for its realization. To be patentable, an invention must be new, useful and different from what would be expected by those skilled in the art”.8 In this definition, invention is even equated with innovation. Invention is often placed in the fields of technology and engineering. With invention, the main focus is on solving a specific problem, improving an existing solution or finding useful applications for existing tools and materials. For example, what else can I do with plastic? New inventions can build on old inventions. They inspire further inventions. Discoveries and inventions are closely linked and many times build on each other.

Design

The field of design is generally associated with creativity. Design is further used to describe innovation and related processes. Design is widely used in art, engineering and technology – such as fashion design, communication design or UX/UI design. The focus of design is on planning the production of concrete artifacts. Design is therefore a specific type of planning with the aim of creating tangible products.

Innovation

Innovation stands for new perspectives on things, methods or products that have value. It refers to the conscious introduction and application of new and improved procedures. The focus is on the implementation of ideas. Another important aspect of the concept of innovation is human capital.9 Innovations should be able to attract human capital. Successful innovations create new jobs.10 Innovation does not necessarily mean absolute novelty, but is a mixture of emergent processes, adopted or adapted processes and a creative response to changes, challenges and restrictions in the market. This is why we tend to speak of relative novelty here. Even the hundredth startup that delivers us food is very likely innovative in some way. The benefit of an innovation is measured by the economic benefit – i.e. national growth or turnover – that can be achieved with its implementation. Innovation is therefore more extrinsically motivated. The focus is not on originality, but on effectiveness.

Innovations are therefore evaluated from an economic perspective. In 1975, an engineer at a well-known camera manufacturer developed the first digital camera for consumers. The management rejected the product as a niche product and stuck to the original business model, with the main revenue coming from the sale of color film and image development services. They considered the innovation – although it was very novel and useful – to be too risky and unprofitable. The manufacturer had thus blocked its entry into the digital photo market in the long term. The idea seemed too original and not economically effective enough for the company. On the other hand, there are innovations that actually turn out to be too original and not commercially effective. These include, for example, the Evian water bra or the Play-Doh perfume with the smell of fresh plasticine. In contrast to being original and useful, innovation focuses primarily on economic effectiveness.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship does not necessarily generate new and useful ideas. Nor does it thrive on new perspectives on existing markets. It is focused on recognizing valuable opportunities and can determine to what extent a new solution solves a problem, closes a gap in the market and can generate sales. It is about promoting or implementing appropriate and radical change when necessary. An entrepreneur commonly visualizes and implements the solutions and ideas of others by identifying gaps, leveraging information and mobilizing resources to implement her vision.

Ideas are born from ideas. Creativity is not a limited resource.

You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have. – Maya Angelou

Whether I actually discover, invent and design creative products, collect capital for their realization in a creative way or creatively bring them to success on the market. Only a few people manage to go down in history as inventors, designers, discoverers or entrepreneurs. Very rarely does one person fulfill all of these roles and create a unicorn on their own. Creativity is not clearly definable and is subjective. It is essential for survival, part of our everyday lives and a key component of our work as computer scientists. After all, we are professional problem solvers. Important aspects of creativity that we should keep in mind are

- Creativity is not limited to the art industry, it is just as present and relevant in engineering, politics and the IT industry.

- Creativity is not based on pure talent. It is a skill that can be learned.

- Creativity can be fun, but it also involves hard work.

- Creativity often requires specific prior knowledge.

When we ask the question: Is GenAI creative? What are we talking about? GenAI as a creative product of human research and science that it is now being sold as an innovation on the market by numerous entrepreneurs? Of the products – images, texts, videos, etc. – that GenAI generates for us in response to a prompt? The fascinating algorithms that bring a generative artificial agent to life or GenAI as a creative personality in its own right?

Sources

- Creativity and Innovation: Basic Concepts and Approaches, Chapter 1, M. Tang ↩︎

- Developing the Cambridge learner attributes, Chapter 4, 2011, Cambridge University Press and Assessment ↩︎

- Approaches to Measuring Creativity: A Systematic Literature Review, 2017, S. Said-Metwaly, E. Kyndt & W. Van den Noortgate, University of Leuven, Belgium ↩︎

- Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. ↩︎

- Evolutionary Approaches to Creativity, 2010, L. Gabora & S.B. Kaufman, University of British Columbia and Yale University ↩︎

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/worlds-first-computer-bug/ ↩︎

- https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/9789813141889_0001 ↩︎

- https://www.wipo.int/patentscope/en/db/glossary.html#i ↩︎

- Innovation, Human Capital, and Creativity, 2002, S. Y. Lee, R. Florida & G. J. Gates ↩︎

- https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.38834.de/diw_rn02-01-12.pdf ↩︎